This post came from some thinking I’ve been doing in general about what I wrote yesterday (about defining your working ethics) and specifically in response to a lovely and honest comment from Meghan Williams a couple days ago (about how tough it is to be happy for your fellow female creators).

When I was in college and first starting the directing track, I only directed plays by female playwrights with all female casts. I did this for almost three years. It drove a few people around me nuts, even though I was at one of the most liberal colleges in the US, even though there were 6 women for every guy in the department, even though they were great plays well known to many.

I finally broke the trend on my final project in the directing course, our devised piece. I’d intended to use an all female group but for creative reasons ended up changing my mind and cast three women and two men. One of the actresses later confided she was thinking about backing out of the show until I had changed my stance on that.

Initially, I actually wasn’t trying to make a statement. I really just didn’t see as many men who I wanted to work with. I was low on the director totem pole and figured I’d get way better performers if I used the glut of women that hadn’t gotten a role in one of the department projects. I liked working with a lot of those people so I decided to do it again. And again. It was super weird. I remember being on break one semester in an acting course in which we literally had to find a creative solution to triple cast the sole meaty female in Brecht’s Man is Man while an actress gave me shit for doing another all female play.

And the weird thing was that I too started to doubt myself. You should make the best art, not art that just makes a statement. But now I think, what the hell, why does it have to be either or? And why does it make us so uncomfortable? Is there a world in which a female dominated production would provoke the same sleepy non-awareness as the plethora of the plays with 75% and up male dominated parts? Why is it a statement?

And the worst of it is that it is not the dudes who are the sole problem.

Is this not the most depressing thing in the world? Read the details, they’re too varied and complex without dominating this post, but do read them. One finding researcher Emily Glassberg Sands cites that is especially depressing to me:

Sands also sent out four previously unseen scripts by prominent female playwrights — Lynn Nottage, Julia Jordan, Tanya Barfield, and Deb Laufer — to artistic directors and literary managers nationwide. Each script was assigned two pen names, like Mary Walker and Michael Walker. The results were surprising: Female readers rated scripts with female pen names 15 percent lower than those with male pen names, while male readers rated the scripts equally.

What!?!

Sand also used box-office grosses for Broadway plays over the last decade to measure economic success and audience appeal to show, for example that:

Women represented 60 to 70 percent of ticket buyers, and plays written by women sold almost one quarter more tickets per week than those by men, earning 18 percent higher grosses weekly. Yet even though plays written by men tend to earn less, they ran about the same amount of time as those by women.

Sands ultimately concludes that in fact there are in fact just fewer female playwrights, likely due to the many forces that disincentivize women to write plays. The ones that do, though they tend to write more female parts than men, often create smaller cast sized works to appeal to theaters.

There are bajillion books about female socialization and the toxic ways that gender stereotypes wiggle their way into our brains against our wills. I’m not going to try to break down the complicated dynamics that exist between women interacting with each other socially and professionally. But I do think it’s safe to say that there are clearly a lot of influences that can affect how women are treated in the world, especially how they are treated by other women.

I don’t think competition is a bad thing. I love to beat other people. I really like working hard to get better and there is no easier way to motivate me to do that than with a racing partner. What I don’t believe in is an unfair race. And I really hate the idea that I’m part of making the race unfair.

Take an anecdotal mental walkthrough of the major theater companies in town. We are not overwhelmed by dudes running theaters. Philly is pretty luck that way: to have a decent sized high level talent pool of women running companies and directing work. This has not always been true and is not true everywhere else.

Now take an anecdotal walk through the productions you’ve seen in the last year. I listed 10 Philly theaters off the top of my head, trying to come up with a mix of small to large in sized. I combed the online records of their last completed season (2011-2012) and made a list of the playwright, director and actor gender break downs.

Wilma – Playwrights: M 3 F 1 Directors: M 1 F 3 Actors: M 21 F 10

Arden – Playwrights: M 7 F 1 Directors: M 8 F 0 Actors: M 36 F 22

Theatre Exile – Playwrights: M 3 F 1 Directors: M 2 F 2 Actors: M 9 F 3

Simpatico – Playwrights: M 2 F 1 Directors: M 1 F2 Actors: M 14 F 10

Lantern – Playwrights: M 4 F0 Directors: M 3 F1 Actors: M15 F8

Flashpoint – Playwrights: M 2 F2 Directors: M 2 F 2 Actors: M 7 F 6

PTC – Playwrights: M 4 F0 Directors: M 2.5 F 1.5 (One show co-directed) Actors: M 19 F 4

Plays &Players: Playwrights: M 2 F 1 Directors: M 1 F 2 Actors: M 12 F 10

Ego Po – Playwrights: M 1 F 1 (Note one ensemble script) Directors: M 2 F 1 Actors: M14 F 10 (This number is short four unnamed actors who’s gender I couldn’t find online)

Azuka – Playwrights: M1 F 2 Directors: M 2 F 1 Actors: M 7 F 9

TOTALS – Playwrights: M 30 (75%) F 10 (25%) Directors: M 24.5 (61%) F 15.5 (39%) Actors: M 154 (63%) F 92 (37%)

Does that shock you? The sad truth is, probably not. I would guess this is not atypical. But it should. It should horrify you.

I don’t think the people who run these theaters are doing this on purpose. But this is what I meant yesterday when I said you need to define what’s acceptable and know when you’re doing something that isn’t. Do you believe that women are 2 to 3 times less talented and capable of being writers, directors and actors? Of course not. But that’s what’s essentially being born out in this trend.

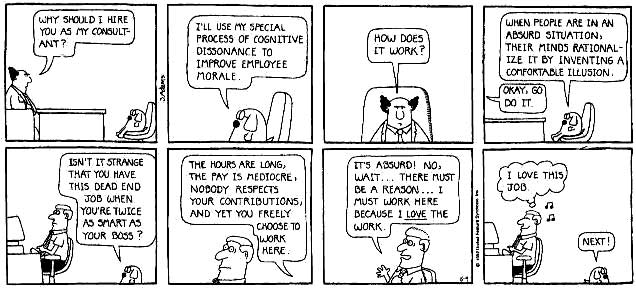

Listen people, especially you female artistic directors, we can’t keep going along with this. We need to point out that it’s not cool. When we’re in positions of power we need to work to do better. We all need to confront a little dissonance.

“But it’s the cannon.” Too damn bad. Make a new goddam cannon. Is the cannon worth diminishing more than 50% of the population? Is it worth undervaluing their stories 3 to 1? No, it’s not. And we need to pay attention that choices we make professionally will determine whether this trend continues. We have to do something. Even if it’s hard. Even if it’s initially unpopular. (Though according to statistics, it won’t be, remember that female playwrights sell 18% more…)

I’m not saying down with men. I’m saying we need to balance this shit out. You want to produce a male playwright. Fine. Do three female playwrights for your following shows. You want to do a Shakespeare (aka dude heavy) show? Go ahead, but you better dig up a ton of pieces with badass female parts to balance the cosmic spectrum. Read a ton of plays by women. Decide to produce them at a higher percentage for a season or two or twelve. Intentionally hire some more female directors. Pick the show with a balanced gender ratio. And if you’re an actor for hire who doesn’t have a hand in programming, FIND the incredible plays by and about women and send them to the people that do. Write about how amazing they are and why they are so important to produce and demand they do so.

We are all responsible. We all need to teach the larger community that this is the kind of theater you believe in. Because if you aren’t you’re teaching the opposite. If you don’t create room then there will never be space for this to happen in the future. If there is a city it could happen in, I’d bank on this being the one.

Come on Philly. Say fuck yeah, we NEED some amazing fucking plays that are all or mostly women. And we need to do enough of them so that the next generation of directors don’t have to feel weird if they happen to choose a series of all women pieces. Not because they are super feminists. But because THAT’S TOTALLY NORMAL. Just as normal as if I’d happened to do Zoo Story, Art, or Glengary Glen Ross.

A

PS – In the the spirit of disclosure I thought I’d share breakdowns of works I’ve been had a major hand in shaping. Obviously the director stat is moot but here are their breakdowns by performers:

Ink and Paper – 1 woman

Joe Hill – 6 men, 1 woman

Echo – 2 men, 2 women

recitatif – 2 women

Giant Squid – 4 men, 1 woman

Owning Up to the Corn – 1 man, 1 woman

Neverboy – 1 man

Master and Margarita – 2 men

Purr, Pull, Reign – 3 men, 7 women

SURVIVE! – 3 men, 2 women

Lady M – 12 women

TOTAL: 22 men, 29 women

If you look at those same works for playwright collaborators it’s about equal in split (depending on what level you count ensemble members) between genders.