Recently, I attended the National Performance Network conference.

Did I mention that I am the worst at networking?

I have learned (for professional survival) how to hide it, but I am deeply introverted at my core. The amount of time that I can spend alone is staggering. I have deep-seated angst about having to do things like call strangers on the phone. And the ultimate trial of my life has been trying to act like a functional human being at a cocktail hour.

Even thinking about it right now makes me a little shaky.

I have always had trouble understanding how other people work. When I was ten my mom consistently had to remind me that other people didn’t see my emotions so if I felt strongly about something, I had to tell them. It never occurred to me they wouldn’t know. Right around the same time it flashed into my mind that if other people couldn’t see my feelings, they might also have ones that I couldn’t see either.

That one still trips me up.

But in a weird twist of fate, I have chosen a professional that requires by its very nature, my constant and vigilant attention to try and decipher how and why people do what they do (so I can show it onstage) and what they will think about seeing someone else doing it (so that I can gauge the audience offstage). Perhaps it’s my own unconscious mind’s attempt at self-correction.

Anyway, I went to this conference and between the awkward conversations over bad drinks and boxed lunches I found myself slowly winding down. Like a phone battery losing power, over the course of three days I worked really hard to stay interested and upbeat and try to charm and chat my way into the hearts of presenters across this nation. I looked over the booklet to see which breakout sessions I should watch for and selected them for maximum pay off potential. But by the last day, around the moment I was thinking, “Ugh, I am so very happy I don’t have to do this any more” I had to mentally gave myself permission to stop trying so hard.

And on the very last day, after the very last session, in the very last hour I thought I would have to talk to people, something happened that totally caught me off guard: I found myself in a genuine conversation.

A few of us locals – Ben Camp, Shavon Norris and Jen Childs – were sitting near each other after the end of a discussion session about the function of comedy in theater. We started chatting about grants and funding and making a living in theater and so on and so on. This guy comes over and started chatting with us. His name was Adrian Danzig and he was a theater artist in Chicago and he too was pondering these kinds of questions with thought and care.

If you aren’t aware, Adrian Danzig is a mother fucking bad ass of a clown.

He is someone who I spotted early at the conference and thought, “Four words, Adrienne Mackey. You need to get over your anxiety enough to say four words. ‘I love your work.’ And then you can walk away.”

And here I was suddenly, with no effort, talking about all the things I care and think deeply about with my peers and one of the very people I wanted to meet at this thing: everything from how non-profits drive and change our work, to the trickiness of collaborations, artist versus administrator brains, to the need to value the time and energy we spend.

We were kicked out of the room and moved to a lobby to then tackle sustainability in the arts and how one grows up and into (or out of) a company and the work it takes to make a life in the arts that means something and doesn’t squash the things that matter. The experiences that shape that meaningfulness and how to create new ones for the future. Why to make new, mutable, imperfect, ever changing work in the face of the great classics (favorite quote of the evening “The best clowning is in the future”).

At one point in the middle of conversing we hit upon the new and amazing program that the Doris Duke Foundation has started. The award provides a lot of resources to really talented people and in one of the other sessions the program officer was telling the gathered group that even the Board of Directors was at first skeptical about this idea of handing artists a ton of money.

I commented that it made me sad to think that even this collection of people, those who are at the very forefront of what it means to value the art making process didn’t trust our capacity to be responsible. To which Shavon replied that she didn’t think it was a lack of trust. It was simply a lack of understanding. That the people who were on that board were likely not artists. That the artist mindset is so different from the way almost everyone else in the world makes money.

Most people work really hard to make enough so that some day they can spend all their time doing what they really want to do. Artists begin by spending all their time doing what they really want to and then work really hard to make enough money to keep doing it.

Of course the board was suspicious. When the average person wins the lottery what’s the first thing they say they are going to do? Quit their job. Logically, the board should worry that if they give artists a ton of money they’d act like most people. And quit their jobs.

And after hearing that I thought, I’m ten again. I have no idea about other people at all.

Somehow at the end of all that talking we landed on the deep and primal nature of vibration and its ability to connect us to everything else that exists in the world. We started at money and ended at the infinite. Which is really the way that conversation’s direction ought to flow, don’t you think? Too often it feels like talking about art heads in the other direction.

And at once we hit the entire universe the conversation was done. We all got up to go. And just before he walked away, I managed the courage to run up and say something to the effect of:

“OhandbythewayIreallylove500clownandI’mfromChicagoandyouguysareawamazingsothanksand… I love your work.”

And then I walked away.

It takes a bit of work to remember that to choose a life in the arts is to offer yourself the gift of doing what you want to do. Artists eat their fulfillment as main meals instead of saving it like life’s dessert. In the daily doing of it, you can lose sight of that fact.

Some days, the infinite and four words is all it takes to remind yourself.

A

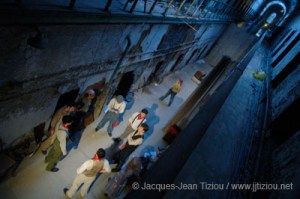

PS – As per usual, JJ Tiziou (www.jjtiziou.net) for the photo