If you give me an ear, I will give you eyes with which to see.

– Kahlil Gibran

True story.

Two years ago, I took a shower. I had just purchased a house in south Philly, most of which needed some major rehab. As such I, and all of the stuff that went along with me (including my fiancée) was confined to one large front room in the house on the second floor. I slept there, ate there, did all my work there. It was, in essence, a studio apartment in the middle of a three-story row home.

I say all of this to so that you can understand that though technically this space is now my living room, I was very comfortable there. Unlike most living rooms, I did my most intimate things there. In other words, I was actually living in there.

Which is why I was walking around in it naked. That and it was summer and hot and I was still adjusting to a living space without air conditioning.

It was a Friday morning and as such, was trash day on our block. And I realized this with sudden vehemence as I, naked and sauntering through my living space, walked near to the windows to grab something and made direct eye (among other things) contact with a garbage man outside.

He smiled, nodded and gave me a thumbs up.

It took me a second. Probably a couple. I was a half second away from giving a thumbs up back. Like I said, I was comfortable and in my domestic space, I wasn’t thinking about myself in the subtly different way I do when I imagine myself being seen by others. So it took me that long to realize what had happened. And as best as I can construct the thought process went something like this:

“That guy can see me.”

“I’m naked.”

“I’m a girl.”

“There’s a guy outside looking at my boobs because I’m a girl.”

“I should back away from the window.”

“We really need to get some blinds in this room.”

The truth is, I don’t really care that the garbage man saw me naked. I mean, I guess in a world where I could go back and redo anything that ever bothered me, I might, at some point, go back and erase that event. But on the list of things that I regret or would change about my existence, this is on the very very low end of the list. It’s one that probably wouldn’t be worth the energy to undo.

I don’t usually think about this moment and when I do, I don’t reflect on it with a whole lot of shame or embarrassment. I’ve categorized it in my mind as a silly thing that happened a couple of years ago. But when I was trying to think of a way to introduce the second half of the post for today, it kept creeping back into my mind. Not because of how I see it now after processing it, but for the way I felt the very moment after it happened.

I kept remembering how in that moment before this guy looked at me and I looked back at him I was just “Adrienne”, wandering around my apartment thinking about the day and the stuff I had to do. And then in the moment right afterwards, I was not just Adrienne but “naked female Adrienne” who had been seen (ogled? admired? violated? made to feel beautiful?) by some sanitation worker because I got too close to the window. I kept thinking how aware I became of this one particular aspect of myself. And in thinking about it now, I remember how vividly in that moment I became so aware of the two sets of eyes through which I could view this event.

There was one part of me that looked at this situation in that moment right afterwards and saw no big deal: just a naked person walking past a window that someone sees and makes light of. And there was another part of me that felt different, uncertain, and weird and saw this as a potentially troubling incident: a woman alone in a house who is stared at and then evaluated (thumbs up!) and potentially left feeling sexualized in a way she didn’t agree to.

At moments like these I have a tough time knowing which set of eyes to use. And I’m using this moment as an illustrative point because it helps me try and quantify something that is really difficult to say with clarity or the depth with which I feel it:

It takes work to view the world with dual vision all the time. It is hard to know how and when to apply that second sight.

If somehow I could run this experiment again as a guy standing naked at the window would I think about the fact I was a naked dude or just that I was naked and too close to the window? Would I interpret the thumbs up as a “hah hah, caught you naked, oh the things you see as a city employee” droll little interlude or would I get a creepy “I’m staring at you and personally up-voting your sexy nakedness” vibe? Would it have gone down the same way or been different? And above all – even if I could know that his reaction was in response in some amount to my gender – do I have to care?

Is this something that should bother me?

Sometimes it takes a new vision or angle on something very familiar to know that it is something that should bother people. Sometimes we normalize things we shouldn’t and it takes some one who takes a step back to say “Uh, what the hell? Why aren’t we all seeing this?” It’s awesome when those people do that for us who have the luxury not to notice. But it’s a lot to ask of those second visioned people to do all that work alone.

Are there situations where people are legitimately undermining or diminishing someone based on their being a woman? Yes.

Are there times when someone is undervaluing female perspective or representation without realizing it? Of course.

Are there times when choices are made that coincidentally result in unfair gender balance that have nothing to do with gender at all? Absolutely.

I can’t remove the lens that constantly evaluates the world this way. So when I, or anyone with an outsider lens that they view the world with, witnesses something that is potentially disturbing, it it is real mental work to try and suss out which of these scenarios is at its core. Sometimes you’re not sure which is happening. You don’t want alienate people that you care about. You want to believe they aren’t doing things that hurt you on purpose. But you also don’t believe you can let them continue to make this mistake.

It’s a super tricky dance, deciding how to proceed. That takes effort.

And I’ve mentioned before that sometimes it’s tiring to try and figure it out alone. Sometimes, you just wish you could hand that lens off for a little, try and put it into a forum for debate, and try to ask the people that don’t usually bother to shoulder that task to take up the burden for a little bit.

This is an attempt to do that. It’s an attempt to make the problem of gender imbalance that I see in theater not just a “female” problem but a communal one.

You didn’t give me your ears, but I’m grabbing them anyway. It’s not meant to be an attack, but it is meant to try and give some people that may or may not being making choices intentionally the eyes with which I’m seeing things. And I’m doing it with numbers and graphs because it feels like it’s a little easier to get you to look with my eyes that way.

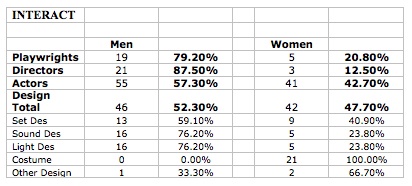

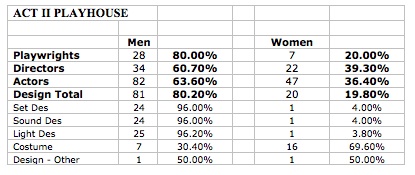

Over the next few weeks, I’m going to roll out data on gender breakdowns over 6 seasons (12/13 through 07/08) of playwrights, directors, actors and designers in Philly theater productions. I think the numbers speak for themselves in many ways, but at some point, I think I will also add some thoughts about how we might interpret such data and what could be a productive set of actions that might result from it.

So here goes

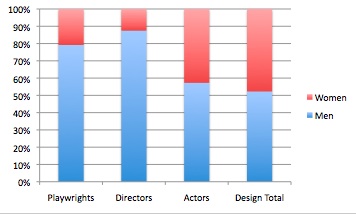

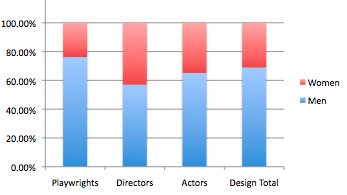

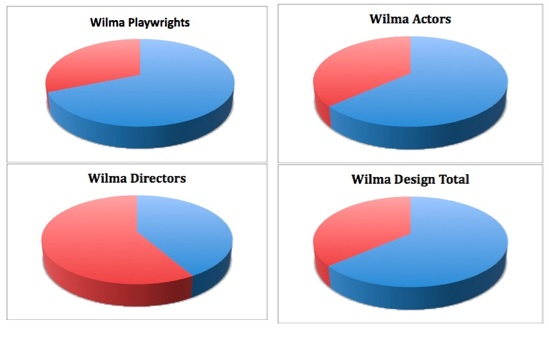

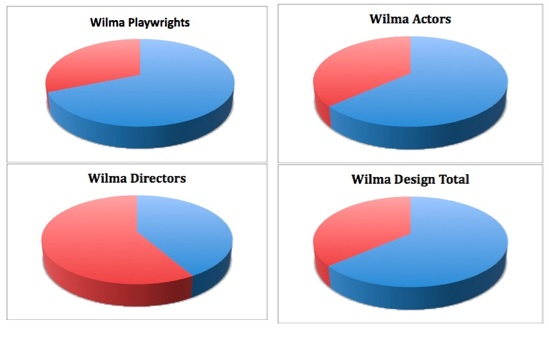

I thought it might be illustrative to start with four of the largest and most visible non-profits. Below is the raw data with percentages and a graphical breakdown for The Arden, People’s Light, PTC and The Wilma. In all cases the graphs are totals of all 6 seasons of productions and blue in the pie chart indicates men and red indicates women.

ARDEN THEATRE CO.

Philadelphia Theatre Company

The Wilma

There’s an awful lot more blue.

A

PS – Some notes on methodology:

1) These numbers are based, when available, on information provided by companies on their websites.

2) For any info not listed online by the company itself I have searched online reviews to confirm missing information, ideally from more than one source when possible.

3) Many seasons (most especially the current one) have incomplete listings and are indicated as such in the raw season by season data (which anyone is welcome to request).

4) The raw numbers indicate a slot in which a male or female is chosen to fill a position and not total number of different individuals hired. In many cases the same person directs, acts, designs, etc multiple times at a venue.

5) In the case of adaptors, translators, and multiple authors I have evenly split writing credit across all names listed. While I recognize this may overvalue on creator’s input from the reality of a particular project, I believe that will balance out over the entire data set and removes me from making personal judgment calls. For example, in a translation of a classic work by a male author with a female translator I would give .5 playwright credits to each gender. For musicals I have similarly split credit among composers and lyricists.

6) For ensemble-generated works I have excluded playwright credits unless specifically listed.

7) Shows calculated are those that are listed as part of their regular season. Benefits, special events, and fundraisers are not included.

8) I have listed designers as a combined figure but also shown breakdowns by category which differ vastly in some cases.