When I started writing on this blog, it felt like I was pouring out a lot of the things that I had been feeling for a long time. The first posts were thoughts and arguments I’d been having a lot – internally with myself and externally with others – and were pretty well formed in terms of their reasoning and logic by the time they went onto (virtual) paper.

In the last few months, however, things have slowed. That’s partly (perhaps largely) due to my busier schedule of work. But I think it’s also because I’ve started to dig deeper into some of these things, I’ve begun to get at the stuff under that stuff. I’ve started to get at the things way down that one may not really realize. When you really start to pull apart your choices you start to see the unnammables that work on you, the things that you didn’t totally even realize were there. When you get down into the real muck of it, this stuff is less formed and harder to parse out. You start to pull apart shit that is often much much trickier to unravel and reason through.

I think this might be where some of the real scary stuff is.

I think this is where the less polite stuff is.

I think this might be where people could get a little upset.

But I think this might be where some of the real work is. And I think this might be the place where you start to tackle the issues that really might make a difference. All of which is to say that this post is coming back around to some of the women in theater/gender parity stuff. This is a first step at trying to dig into the muck.

Let’s begin with the truth: we have some major work to do. Even those of us with the best intentions aren’t really fixing this problem. Those of us with cursory intention are likely perpetuating it. We can blame the theaters that continue to produce plays with way imbalanced seasons. We can bemoan the writers that continue to create the plays. We can lament the market for having a glut of women. We can do all these things. But it isn’t going to get us anywhere. And if we actually want to get somewhere we have some “money where our mouths are” choices to make.

Backing up a bit: I had an argument back in mid-April, right around the time I wrote this post slamming a few Philly reviewers for their presentation of women in Shakespearean roles. This argument, one that had seven months ago is still picking at me and has been ever since I had it. It would randomly surface in my head in the middle of rehearsal, while driving, watching TV, I just couldn’t let it go. Couldn’t let it go because at the time I had it I was trying and failing to say something, something that I felt with incredible force and vigor and anger and fullness, something that felt like it implicated me and in the way I make choices about my work, and frustratingly was also something I felt totally unable to articulate.

The argument was a sweeping one, the kind that starts with a couple offhand comments and ends up gobbling up an entire afternoon. It was the kind of argument you can only have with someone that you really trust, because you actually start to uncover defenses. It was the kind of argument where you talk about the things you believe deep deep down inside about yourself and the world around you. And my sole caveat here is that it’s totally impossible to try and reconstruct all the things we said. But basically, it came down to this hypothetical:

If you have a slightly better male artist and a slightly worse female one, should you pick the worse one to help achieve better representation of female artists?

In the moment of the argument, it felt like I had no choice but to argue for the latter. It felt like a mission from on high. Like my entire life depended on making the case for that female playwright. That there was something deeply stacked against her. That I was the only way she was going to get a chance and if I couldn’t find a way to make that choice seem reasonable and obvious to my argument partner that she and no female writer after her would ever get it.

Which of course I failed to do.

And of course there are (and were) many reasons one could counter the position I took. Rational, reasonable, intelligent and thoughtful positions that we went back and forth and back and forth about. I almost ended up in tears because sitting there I felt so torn between the opposite side’s reasonableness and some kind of irrational deep down feeling that said there was something very wrong about taking a side other than the one I was on.

Neither of us could be moved. We left it unfinished.

But as I said, this question and the debate that ensued has continued to stick, continued to hang out in the back of my mind, needing to come to completion. It’s been this nagging incomplete thing trying to resolve itself for seven months now.

Over time, small details begin to accrue:

An review for a work of my own in which women played “men’s” roles

Writings from the dear Katherine Fritz

A book on the virtues of affirmative action

And then finally this: a study in PNAS about gender in the sciences that both control for and show statistically validated evidence of bias from Corinne Moss-Racusin and her colleagues at Yale. It was this last one cracked something open that I can hopefully finally start to put into words.

Here’s an intro from Sean Carroll’s blog for Discover:

Academic scientists are, on average, biased against women.

I know it’s fun to change the subject and talk about bell curves and intrinsic ability, but hopefully we can all agree that people with the same ability should be treated equally. And they are not.

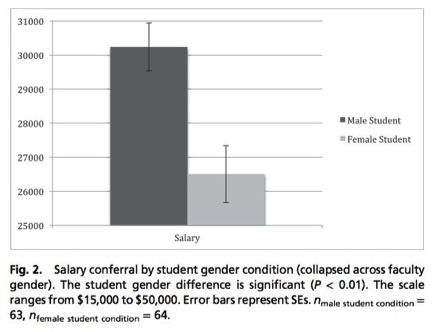

What the researchers did a randomized double-blind study in which academic scientists were given application materials from a student applying for a lab manager position. The substance of the applications were all identical, but sometimes a male name was attached, and sometimes a female name.

With me so far? I swear, this comes back to the arts.

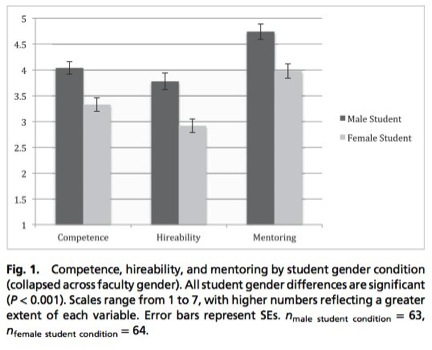

So half of the applications were Johns and half of them Jennifers. What the findings showed were that the faculty members rated John significantly more “competent and hireable” than an identical female applicant named Jen. These participants also selected John to receive a higher starting salary and offered more career mentoring to this male applicant.

And the real kicker? It didn’t matter if the faculty member was male or female. Both were “equally likely to exhibit bias” against Jennifer and viewed her as “less competent.”

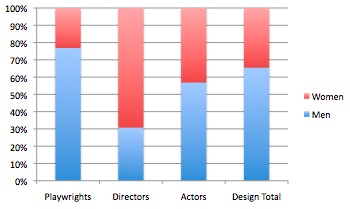

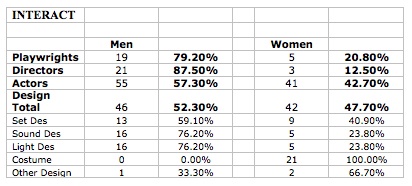

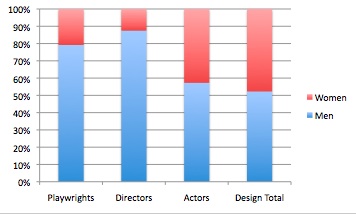

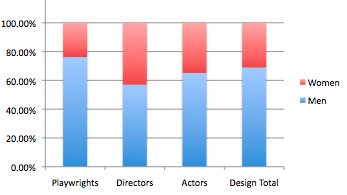

A depressing graph:

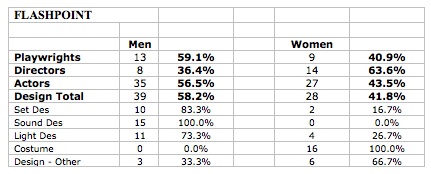

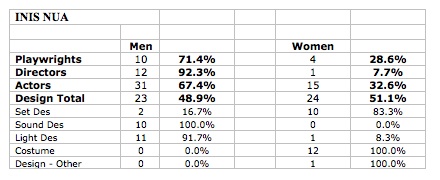

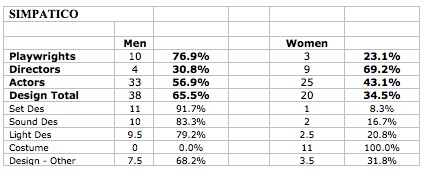

How about another?

In her great Scientific American blog post about this study, Ilana Yurkiewicz appropriately writes:

In her great Scientific American blog post about this study, Ilana Yurkiewicz appropriately writes:

Whenever the subject of women in science comes up, there are people fiercely committed to the idea that sexism does not exist. They will point to everything and anything else to explain differences while becoming angry and condescending if you even suggest that discrimination could be a factor. But these people are wrong. This data shows they are wrong.

The thing that stuck with me about this study, maybe even more so than the disturbing results themselves, is that, as Yurkiewicz points out, the scientists didn’t view gender as a factor in their decision-making. They thought they were using objective data for their assessments – rationally reasoned, non-gendered arguments – to determine the strengths of this particular candidate for this particular job.

I’d bet my house that were I to get into argument with those interviewers of Timon of Athens that the points they would have countered with would been rationally reasoned, non-gendered arguments. And my point is that just because you don’t obviously act like a sexist or consciously espouse anti-female philosophy doesn’t mean it isn’t working on you. And even the benefit of experiencing that disadvantage is no shield from inflicting it on others.

Does anyone want to guess about whether I think this pattern might be found in other contexts?

If it can happen so sneakily in something as cut and dry as the representation of skills on a job application with the exact same credentials but a difference of –en versus -ohn at the end of a J…

If there are forces that bias us against thinking that a woman is as capable and intelligent as a man in doing a job in such a carefully crafted scenario of objectivity…

If that can happen in a field whose express purpose is to remove bias from its methodology…

How can we possibly imagine that we can create object assessments in all the incredible number of variances and nuances and details about what makes a better work of art?

So of course if you knew for one hundred percent sure that you were absolutely judging the work objectively then yes yes yes yes yes you should absolutely pick the “better” play. But I what I’ve come to finally articulate these seven months later is that I just don’t believe there is anyone in the working world that can honestly say that they can do that.

If you have a slightly better male artist and a slightly worse female one, should you pick the worse one to help achieve better representation of female artists?

The problem isn’t your answer to this question. The problem is that this is how the question seems to always be framed. And I don’t buy this scenario is really the one that any of us is objectively encountering.

So when I hear “It just turned out that way,” I’m calling bullshit. When I hear, “The season line-up just ended up male heavy,” I’m calling foul. When I see foundations that just “happen” to be given to a majority of male-driven companies, I’m not going to say “Well that must have just been the applicant pool this year.”

We all know the odds are already stacked against women because we see it manifest all around us. And while the scientist in me wants to document and collect all the evidence I can to try and display this finding to the world, the maker in me says I need to find a way do something about it now. I don’t have time to wait for a fix. I don’t have time for more research. I’m making my work right now. And there’s no thinking theater artist I know who would truthfully declare gender wasn’t an issue on the general scale. Where we break down is whether we are willing to acknowledge that it’s happens in our own personal choices.

Intentionally or not, like it or not, we are all making a million tiny anti-women decisions and justifying them with million other reasons. The troubling implication from that PNAS study is that we not only judge women’s past work less fairly but that the bias impedes the potential for future opportunity. And without opportunity we are less likely to create new examples in which people can start to see anything different. Every performer or writer or director knows without a chance to make anything you can’t get better at making things. Even if you wanted to work way harder to achieve the same perception of success it’s going to be way harder to find the opportunity to do so.

And here’s where I’m going to get honest with you all.

I think a lot about this. I try very very VERY hard to root this shit out at the source. But I know I do it too. I wish I didn’t. But it’s just… in there. And were I able to somehow analyze my seemingly objective rational non-gendered artistic decisions I bet I’d find that I too have subtly undercut women in my process or in the field as a whole. Though I might not see exactly how those predisposed biases slip in, I know am not immune. And neither are you.

And in knowing that, I have felt myself at a cross roads where it seemed like I was asking this question:

If you have a slightly better male artist and a slightly worse female one, should you pick the worse one to help achieve better representation of female artists?

And increasingly, over the last decade of my career I’ve forced myself to do the thing that felt, in some vague and hard to define way, the slightly less artistically “right” choice because I believed it was the better moral one to make.

Just so that I’m totally clear about this:

I’m saying that I have steered projects in artistic directions that I might not have otherwise had I not cared about making a less imbalanced world through my theater. I have often picked the slightly “worse” artists because I believed it was the morally right thing to do.

And I do it constantly. I do it on projects ALL the time. Not just on the ones where it seems obvious. I make myself go against my gut in lots of choices because I think it’s better for theater as a whole.

I don’t often don’t say that out loud.

In fact, I don’t know that I’ve said it to almost anyone before now.

And part of the reason for my artistic public persona – my warrior-queen-who-get-all-the-grants-and-deserves-them-because-I’m-a-badass-take-no-holds-creator stance – is to show that despite doing this you cannot impeach my creative process. I want to demand that people acknowledge my artistic worth. And I do that because I secretly fear that people will see what I’m doing and think less of the work. Because deep down in the muck I fear that most people think women are not as artistically capable or that their stories are not as interesting.

In the past I’d get really hung up about it. I’d worry that I was losing my sense of artistry in order to make a point. And though I still believed it was worth it, I fretted about the cost.

I used to think that I was trading quality for principle when I did that.

Now I’m just going to think, “Jennifer.”

Perusing the outcomes of those choices here’s what I find: way way way more often than not, the person I picked was able to bring something to the table that was tangibly better. For obvious reasons, I am not pointing out specifics here but suffice to say, when I went with that slightly non-gut choice, I was often rewarded back in spades. And even when I wasn’t, if I could remember to view the failure in context of the qualities of the artist’s work and not simply their gender, I almost always saw that the real issue had little to do with them as women.

I’m not saying you have to pick terrible performers. I’m not saying you can never work with who you want. But I am saying that creative worth is totally squishy. I’m saying that we make artistic assessments for all kinds of totally ridiculous reasons. I’m saying that the way it’s usually is done is a massive amount of momentum pushing you towards a choice. I’m saying that we’re probably wrong as often as we are right about how a collaboration or an artistic impulse is going to work out. That failure is built into our creative growth. I’m saying we might as well start being “wrong” for the right reasons.

I’m saying that if you do this for a living, you have to know that so much of the time the difference between two options in the scope of a whole process doesn’t mean that much in the long run. I’m saying the difference between “really good” and “just a little bit better” is likely negligible. And perhaps not actually there. And even if it might be, at a certain point, the artistic benefit no longer justifies the outcome.

I’m saying if you’re at all considering a chance to give the opportunity to a female voice or person or story you should do it.

I’m saying if you actually care about doing anything about it, you have to do it. Even if something is pulling you away from it. Maybe especially then. Because that thing that’s pulling is ugly and dark and mean. And it hides in reasonable arguments’ clothing, it hides in gut reactions we don’t quite unpack. The only way to exorcise it is push in the opposite direction. Even when it seems strangely hard to do so. Even when it makes you feel a little funny. Activist-y. Moral high-ground-y. Like you’re doing the wrong thing-y.

Trust that you’re an amazing artist. Trust that this small push in the other direction will not harm your work. Know that it is a better thing for the world to have done. And see that your work is no worse off for it.

And then perhaps we can start actually getting this shit fixed.

– A